“Holy shit, I’m not

going to be able to sleep, am I?” I thought, at 00:34 am, 3450 meters above sea level, in a cabin with a hundred other people. It was warm and it smelled

and people shuffled and made noise or lay with their phones, lighting up the

room. In one and a half hours, I’d have to walk another 200 meters upwards,

about an hour of walking in pitch darkness, only lit by a headlamp.

With several hundred others, here to do to the same.

I was near the top of Mt. Fuji in Japan, in late July. I was there with three friends, and we were hoping to see the sunrise on

top of the mountain. On the very top. That meant walking up there the day

before, sleeping at 3450 meters until 2’o’clock at night and then finishing the

rest in utter darkness, to wait for the big yellow orb in the sky to become

visible.

We were there because we wanted to do it. We were also there

because my friend had played Celeste.*

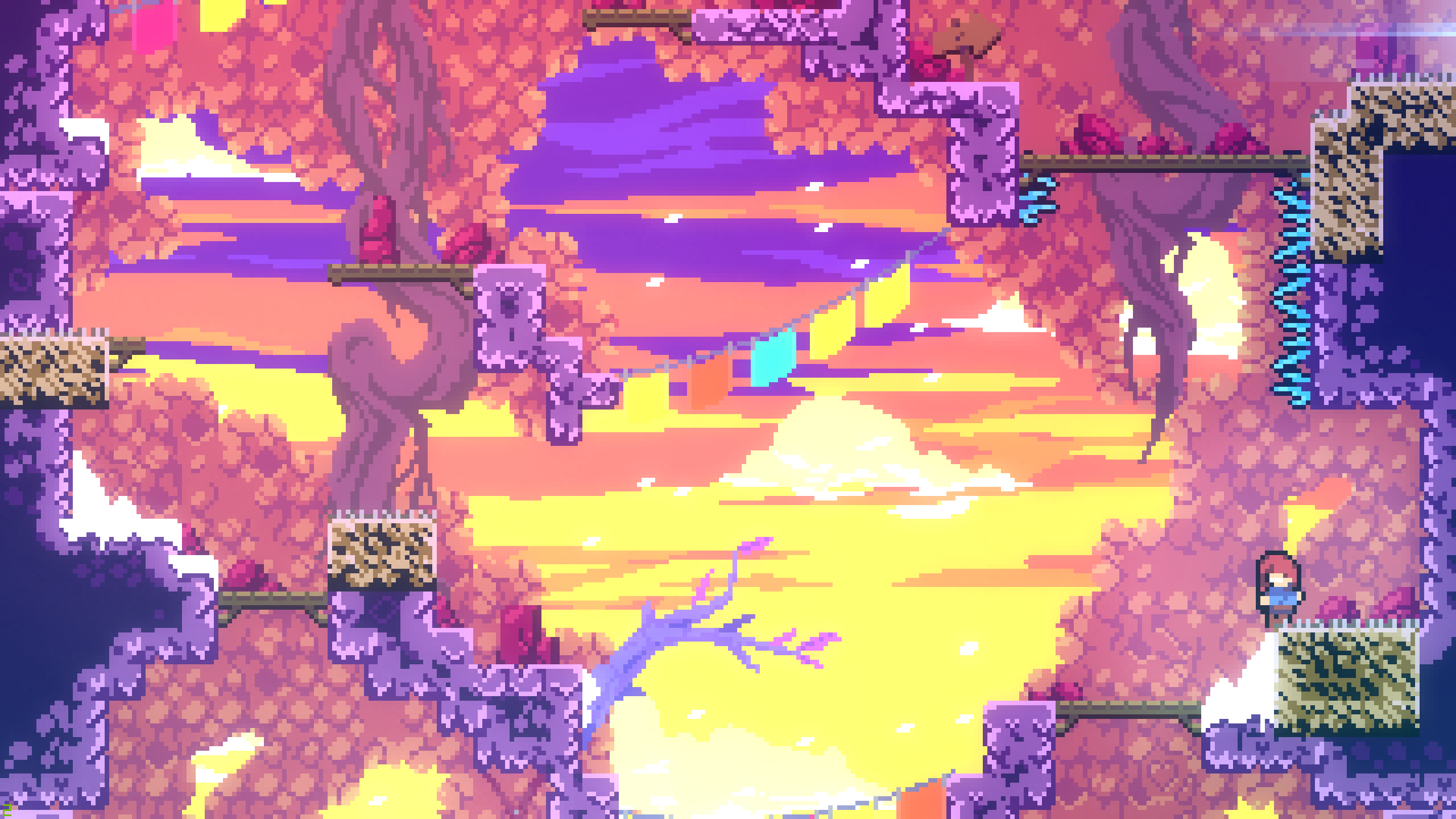

Celeste is a 2018 video game, made by Matt Makes Games (hey,

I didn’t make the name), and is pretty darn good.

It is a pitch-perfect, hard-as-nails platformer about a girl

named Madeleine deciding to climb a mountain. The reasons are not obvious at

first, perhaps even to herself, but it is clear she is determined. That this is

something she must do.

It is a game about self-reflection and learning to accept

your demons.

(Yes, this will contain general spoilers for Celeste,

nothing super specific, just theme stuff).

See, Mt. Celeste (that is the name of the mountain) has an uncanny ability to draw out yourself into the world, and for Madeleine, that reflects as another part of her who smashes out of a mirror. The fight to get to the top is one that is as much against herself as it is the environment, often manifesting quite literally through the gameplay.

And this is a common metaphor, using a literal mountain climb to face your own challenges, to change who you are—to overcome and, indeed, transcend yourself. We often use mountain climbing metaphors when facing other challenges in our life so when we’re literally climbing a mountain, that same language seems… insufficient.

I wasn’t climbing Fuji as a metaphor. I was climbing it, really. And yet, there’s something about this idea that walking up a mountain will lead to a self-reflective experience. To a transcendental one.

And since that day, I’ve thought about what it meant. Whether it was important or just me being some more meters above the sea than usual.

Climbing Mt. Fuji is a task of religious importance in Japan. It is a mark of pilgrimage, and there are rituals surrounded by it. It is the kind of place where one goes in search of a religious experience.

Let me just say, not being able to sleep, and almost

vomiting at 2 am while walking up a mountain at 3600 meters height,

was not a transcendental experience. It sucked. One of the people I was with

did vomit. 3 times.

And sitting in too few clothes, freezing, waiting for over

an hour while the stupid celestial ball slooowlly meandered up behind the

clouds so we could finally see it, also was awful.

But we kept walking. We took breaks when we needed them, and

kept walking.

And then we waited for the sunrise.

Celeste is a difficult game. It does not require the same amount of physical strength needed to walk up a mountain for 5 hours, while you’re tired and the air is thinning. It is difficult in dexterity, of executing a series of button-presses to a precise timing, weaving in and out of moving platforms, sometimes dodging your other self hurling projectiles at you. But they both require perseverance. You will die many, many times in that game (I died 1255 times!) and you will have to try again, and again.

But it always lets you. It is difficult to climb Mt Celeste, and you will have many setbacks, but the game always believes you can do it. You don’t have to do it all at once. But one step at a time.

It was difficult, but we still made it. One step at a time, we got to the top.

It was beautiful. It really was. It was astonishing, grand, astronomical, and affirming. The sun was incredible. There was a literal sea of clouds underneath us that felt larger than anything I have ever seen. I am honestly so happy that image managed to capture just some of the scale of it. It felt so magnificent to look at.

But (and here’s where I can’t help ask the question) did it change me?

Madeleine can only finish climbing the mountain after she begins to talk to her other self, when they both begin understanding each other and why they’re there. She was there to get rid of her other self but realizes instead she must embrace it.

When we got down from Fuji, a friendly man came over to us

and asked if we wanted to fill in a survey about our experience.

Which is the only time I’ve filled in a survey about a

mountain.

But it had an interesting question for this context. I don’t

remember the exact wording but it was something like this:

“Did you experience a transformational / religious moment on the top, seeing

the sunrise?”

The question had three choices: Yes, Maybe and No.

I said maybe.

There’s something odd about maybe having a transcendental experience. I feel like, in

traditional terms, I would either be very

sure I had one, or I didn’t have one.

Yet I hold to my answer.

I didn’t change my life. But I felt something. It felt powerful

to do. It felt worthwhile (did it? It also didn’t feel “productive”.

We walked up to walk down again). I am proud to have done it. And I will

cherish the memory forever.

But is that enough?

That question will always haunt the doubting mind, as there

is never such a thing as enough. Not in our western, capitalist society.

Before they reach the top, when Madeleine and her other part

are working together, she says that it doesn’t matter if they reach the top

now.

“I’m just glad we’re trying” she says.

Which feels weird to accept after you’ve spent so long

trying and failing and trying and failing and are so close.

But what it’s saying is not that we aren’t also glad to make

it to the top, that the top doesn’t matter. But that it’s the trying that makes

us happy. It’s in the trying the moment is made. It is in the difficult act the

feeling is forged.

It took 6 hours to complete Celeste. I’ve already mentioned it took about as long to climb Fuji (if we don’t count the not-sleeping and the traveling to the mountain and all that). And it was 6 hours of trial and trial and trial and walking and walking and walking.

Celeste ends with Madeleine accepting the other part of

herself, and resolving that she will begin to work in concert with her rather

than against her.

It is the kind of ending that befits a story and the kind of

ending that feels final in the way only a story can end. It doesn’t show Madeleine go home and still struggle with

her daily life. See the old conflicts still happening, even if she does handle

them better. It doesn’t show how change is a process and not a switch. (I think

the game is aware of this, it just isn’t part of its scope.)

Someone in a previous writing group of mine had the words

about these kinds of experiences: “Something

that breaks the mind in a way that lets other parts in.”

This didn’t quite do that. I never broke like that.

But it was a difficult thing that I wasn’t sure I could do,

and it was indeed as difficult, and we still managed it.

Life is rarely so storybook that one mountain climb changes

your entire life. But that mountain climb may help push it a little bit.

And maybe that is enough.

* Ok, it wasn’t ONLY because he’d played Celeste. But it was a big factor in him wanting to do it!