Two weeks ago, two people came by my house and gave me a copy of the

Book of Mormon. They asked if I wanted to join their society, or at

least, did so indirectly by asking all the typical questions: What is my

relationship to god? Have I ever done a prayer? Do I believe in

anything? I answered most of them with fairly weak non-descript answers,

but there’s one question in there that made me pause a little.

They

asked the obvious “do you believe in god?” and I, complaisantly, said

“not really” (not wanting to cause disagreement), and they asked “why

not?”

I reflected on it and came up with a brief answer, but now thinking about it later, the question stuck with me: Why don’t I?

There’s

no harm in believing in a god (and now I’m switching away from their

conversation, to talking about any god, deity etc. one can believe in).

There’s no reason… not to, other than perhaps our rational ideas that it

is “highly improbable” that one exists. I didn’t blame them for

believing, and I don’t blame anyone else for doing so (I understand

blaming people for committing violence, etc. in the name of god, but

that is not directly correlated with their belief in the god to begin

with, so let’s not talk about that, yeah?).

Let me preface this by saying that I am not well versed in this

topic: I am not a philosopher, theologian, or otherwise read in

religion, outside my basic high school education and personal curiosity.

This is not a “what god is” conversation, but more a review on my own

thoughts of it, from my western, nordic, white, “rational” perspective.

Please take nothing in here as fact.

If you’ve wondered about this sort of thing before, you might have heard about Pascal’s Wager, which says that it is, rationally, much safer to believe in god than not.

Because if he/she/they does exist, and you don’t believe in them,

you’re probably fucked. But if they don’t, and you do believe, it

doesn’t really matter. So, the safest course of action, is to believe,

then you’re safe either way!

But you probably felt how that argument made you twist a little right? It doesn’t seem rational. It seems the opposite of believing in a god—to us—the “rational”—at least. The argument makes logical

sense, but like any piece of logic we should not take it at face

value—the logic only means as much as the arguments can uphold.

So, the question is whether god exists? An impossible question. Like the teapot,

we cannot disprove the existence of god, a fact that can both be used

and misused. We hardly ever feel their presence (debatable! I’ll get to

that), so what does it matter? My answer at the time ended up being

something akin to that: “I don’t really notice a god”, but of course,

you can punch a bunch of holes in that.

People who do believe say

they see signs of a god all the time; in their everyday life, in the

shapes of the clouds, in their grocery receipts, in their morning

coffee. And, you might disagree with me on this one, but who are we to

claim they are wrong? Who are we to smash them down from their personal

mythology? We all storify our lives to extents, we might not claim it

was god who was behind it but we can still read signs in the way we hit

all the red lights in traffic. I don’t believe it is god sending us a

message, but I doubt I’m the only one who’s thought things fit together a

little too neatly into a story-ready package.

And of course, my

academic mind immediately tells me that that happens not because it’s

the case, but because our minds are designed to weave stories out of

events, prescribe causality where none necessarily is. That’s one of the

things our brain is really good at.

Ok, so we don’t believe in god because we just don’t assign a deity to storifiable events? Because we see meaning in disparate events doesn’t mean we believe a single entity designed them. Yeah? Alright, but what’s our reason for doing that? Why shouldn’t it be? It might as well be? If we’re down to this, it’s a difference in semantics, which is not an interesting conversation.

So what other reasons do we have to not believe in god?

Because it seems silly?

To that I have a very simple message:

Fuck off.

To think that it’s silly is acting in direct defiance to all those

who do, to call a huge population on earth idiots for wanting a larger

context to fit in to (*cough* Dawkins *cough*). That’s just not okay.

I’ll not take that stance.

No, I think we’re dealing with this in the wrong way. Let’s look at god from another perspective.

What Does God Do?

We might ask ourselves, what does a god figure do? In order to describe why it doesn’t make sense to me, maybe I should describe each part of a god’s purpose and define my opinion towards those? (This is not a complete list, by any means)

1. A god has created all in the beginning.

We don’t know what caused the universe to be created, and we have no

idea what was before, other than our best guesses at nothingness. That

doesn’t disprove a god, it doesn’t prove it either—same problem as

before. However, from my perspective, the more interesting question is

“what does it mean if a god created the universe?”

The quick answer

is that there would probably be a purpose behind it, that someone

intended something. We have no idea if they succeeded or not, or if

they’re still trying things.

There’s that idea that Earth is a petri

dish for someone else, that we’re an experiment, a VR simulation, a bet

to see how long it takes us to destroy our planet (so far, on good

track!), and that’d fit right into those ideas—gods, aliens, call them

what you will, if they have that much power, they are gods to us.

There are two possibilities to this scenario: They will interfere at

some point when the experiment is up, or they will not—in either case,

we can do nothing.

Hmm, that seems pessimistic.

There’s the other

aspect to it, the more romantic take, that god created life because it

is beautiful, because it was the right thing to do, because they, as it

says in the Bible “saw that it was good”.

I am not able to determine

whether life, in its total, is good, so I don’t know about that one, but

it is a more sobering thought.

Yet, all in all, it makes no difference whether a god made the universe or not, if they don’t change things anymore.

2. A god knows all in existence right now

But is highly passive with all that knowledge? Maybe knowledge creates apathy.

Looking

at it by itself, knowing something is not impossible—however, knowing

the extreme distances of space and time, I can understand anyone

questioning the plausibility of such a creature. But to that I would say

that just because something is unfathomable for us doesn’t mean that it

is for something else. Maybe there is a type of creature that can

traverse the fourth dimension like we traverse the third. Maybe there’s

someone who can see the fifth or shift between strings—who knows? Don’t

fool yourself into thinking our way of sensing the world is the only one

that can ever be.

3. A god affects life right here and now, it is in all of us and changes things as they see fit.

This

one is more difficult for me to reconcile. I struggle with fully

understanding what it means, at first, and then I realize that those

changes can only ever be subtle, out of sight, individual, personal, or

immaterial. It could not be something provable and strong and visible,

otherwise we’d all know of god’s existence already. If a god wanted to

be known, we’d know. So no, it is all personal, if anything.

And this

is not to say personal experiences aren’t real! They are often the most

powerful kinds of experiences there are, but… I am saying I don’t know

how it affects my life, then, outside of whatever might happen to me. If

I haven’t had an experience like that. Soo… then it doesn’t matter?

Until I “see” a god—until I see the proof of the undisprovable—I might

as well not care either way? (or believe just-in-case)

We’re circling arguments now.

4: Everything is as god planned it, and 5: Everything will be according to what god has planned.

I clumped these because they are similar and equally terrible. This,

ultimately deterministic outlook is flat out wrong. I don’t care what a

god is if they do exist, saying that everything that has and will

happen, happened because it was planned, is bullshit.

It is lazy,

apathetic, and frankly, cowardly to resign to the idea that we do not

control the mistakes we have made—that it was because it was destined to

be so. It is always possible to explain away why something happened the way it did—saying it was god’s will is immaterial.

And secondly, it is a terrifying outlook to believe someone/something

knows the future. It is so easy to become apathetic or nihilistic if

you decide that no matter what you do, it was already decided

beforehand—and at that point it doesn’t matter, because it was decided

beforehand!

That there is no choice I can think of that hasn’t been

thought through, that there’s no path I can take that isn’t already

decided for me, seems… pointless.

I guess it can be rewarding to feel

like part of a whole—to feel like you are doing your part, like you

have “fulfilled your destiny”, but I guess I’m too much of a millennial

to believe there’s one path I have to take.

So, no, I refuse to believe—or more accurately, accept—that god has this kind of power. Regardless, once again, if this was actually the case, we wouldn’t be able to do anything about it. Same, same.

Looking at all this, it feels like god barely matters! If we refuse

to grant them any power of meaningful change, then they might as well

not exist!

Yes, we might be eternally grateful they gave us the gift of life, but if we can’t even thank them, then what does that matter?

I

guess I could end this essay with a simple “it doesn’t matter whether

you believe in god so you might as well not”, but I think that’s also

being cheap.

But what else is there?

Oh, yeah, there’s the whole afterlife

thing… Hm. Again, I guess it feels like surrendering to say that the

important life is not this one, but the next. Let’s just fuck up the

planet, eh? (I think you see the problem there.)

No, the approach needs to be wholly different. We need to go back to where religion matters.

The God We Do Believe In

Back when I was fourteen, I had the choice to be confirmed or not. I

hadn’t been baptized either, so I’d be a process. I began the

preparation, but withdrew a couple weeks in (dunno how it is in other

countries; in Denmark we have a weekly thing people go to in seventh

grade for almost a year, to learn about Christianity etc.).

But I

still wanted the Bible. We were all given a Bible when we started. I

didn’t want to lose mine. You might call that selfish—I’ll grant you it

was, a bit. But there was a larger reason, in my mind, as well.

The Bible is a bit of a magical book—and I don’t mean that in the

spiritual sense, I mean that in the purely affectual power it has a

piece of written text: It possesses a strong quality as a… well, a

story.

You don’t need me to tell you twice that stories are magic.

You already know that. You’ve read, watched or played a story that

touched you, that made you a different person, that made you change what

you do and made you see life differently.

Even if you haven’t read

the Bible I don’t think there’s any discussion of the power of that

book; the amount of people it has changed or influenced.

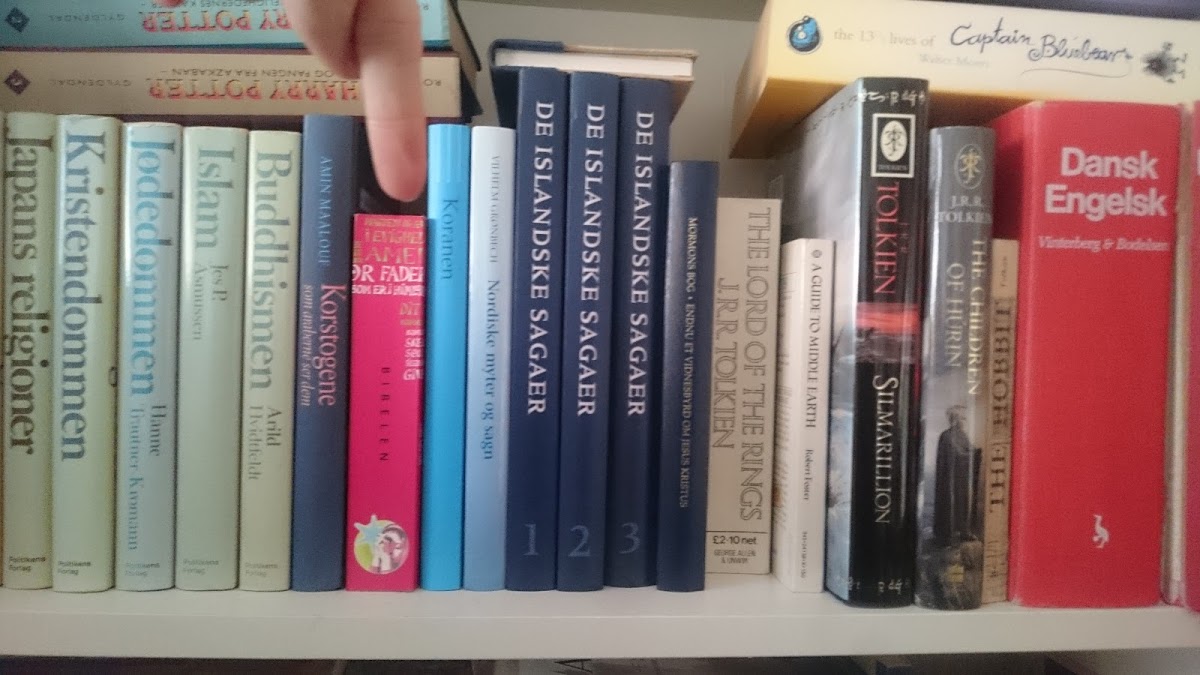

I still have that Bible. Next to a copy of the Quran, the Icelandic

Sagas and, now, the Book of Mormon. Silmarillion is on that same shelf,

too.

I don’t believe any one of those is more powerful than the

other, any more meaningful than the other, and yes, any more The Truth

than the others.

We know there is no reason the Christian god is any

more real than the Islamic, than the Greek gods, than the Norse, than

anyone else. It is not the specific version of any god I would subscribe

to if I were to ever believe, but if I were I would subscribe to something akin to them as written in the texts—in all the texts.

And if we accept, which we should, that the Bible, the Quran, the Torah, and all the others are written by people,

then we suddenly get a very different perspective on what a god is. If

we remove ourselves from the idea that the god exists outside our

view—as I believe that is ultimately meaningless—we can look at a god in

a vastly different perspective.

If we look at god as a human

creation—which would probably be blasphemy in most religions—I feel much

freer to talk about god in a way that makes sense to me.

God, in this way, becomes a way to frame the world, it becomes a way

to see those signs that happens around us, to explain the unexplainable,

to give life to the lifeless, to assign empathy to the great cosmos,

and to accept cruelty.

God is told and written, they are passed on in

stories and in minds, and their relationship to us comes from what we

have been told about them. Their power towards us becomes a consequence

of what we make them.

God becomes a story we tell ourselves.

And that’s not to discredit it at all! I’ll be the first to tell you the power of a story.

It

does not belittle gods to talk of them as stories; it empowers them. It

avoids the silliness, the truncating, the all-encompassing omnipotence

and makes them… something we can talk about. It gives me a framework to

understand them in a context where I’m not questioning the rationality

of my belief. It puts the gods in a place where we don’t have to wonder

what it means if they do or don’t exist—they all exist, equally,

individually, and practically in stories we tell. We don’t have to

question our science if something says god created the world 4000 years

ago and we don’t have to assign creativity to the divine.

And suddenly it sounds like I believe after all, doesn’t it? Suddenly, when removed from what makes god, well… unreal, I don’t have problems believing. It doesn’t matter if we can’t thank them, because we can thank the people who made them. Because here’s the actual truth, that you might have put together yourself, or understand intuitively: God is other people.

Just as well, we exist with both poles simultaneously, and if we have hell,

we must have its opposite too. When we tell a story we talk of

ourselves. When we create art we describe ourselves. And thus, if god is

in the work, and it is part of us, we are the gods it describes.

If

this is a stretch to you, I’d ask you to turn to whatever you believe,

if anything, and ask yourself where it comes from. Was it not from the

people around you who were kind to you, who gave you a place to stay,

who made you feel welcome?

If those people aren’t gods, I don’t know what is.

So, to the original question, I guess my answer is, no, I do not

believe in god in the way you do. I do not believe god is an all-knowing

being that created all, controls all, and determines everything that

happens.

But I do believe in the stories we tell about gods. I

believe in the stories you tell me, and I believe in you when you tell

them.

I believe that god is a story we tell ourselves, and that that is as powerful a statement as any you could give me.