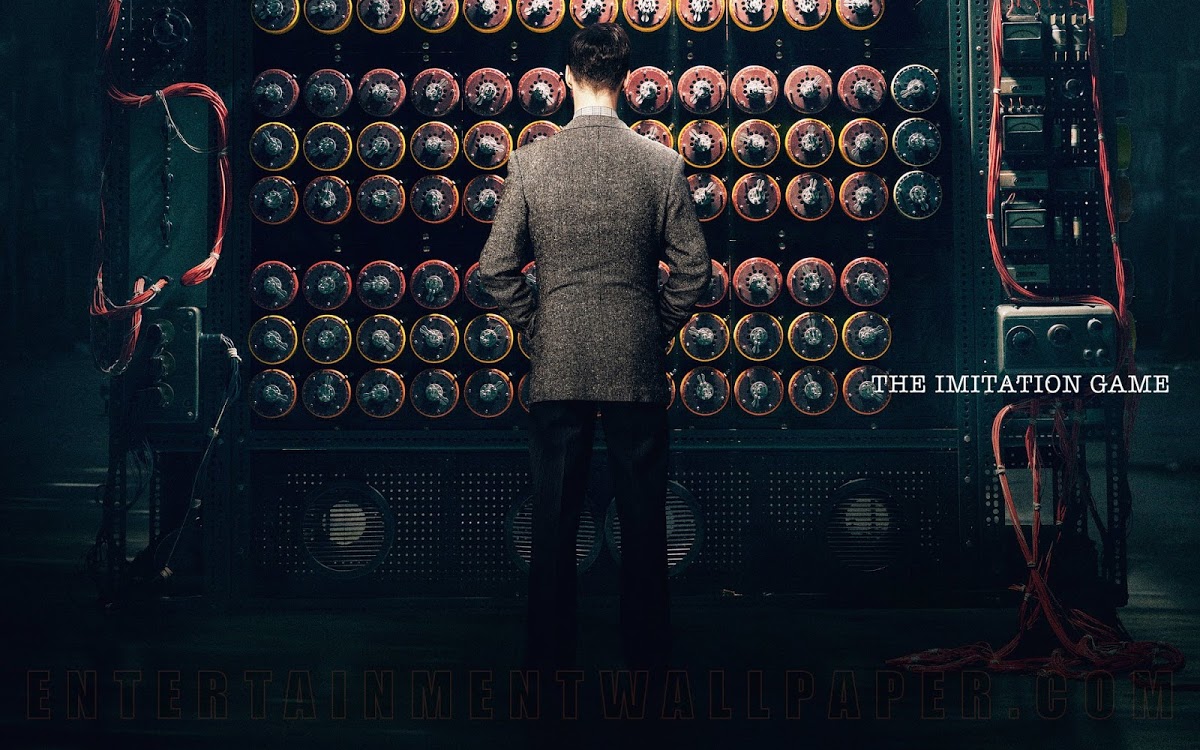

I recently went to the cinema and saw The Imitation Game, which is a fantastic movie you should see about a really interesting person most only know by name: Alan Turing. On top of that, I am also playing through the fundamentally excellent The Talos Principle, which, coincidentally, is dealing with very similar themes, albeit in quite different ways. The theme is, if you hadn't guessed it, AI, machine thinking, and when extrapolated, existential wondering about what thinking and being is in itself.

"Can Machines Think?" That's Alan Turing's first and primary question in the paper he wrote in 1950, a while after (most) of the events of the movie take place. The movie does touch on his concepts present in this paper but he goes far more in-depth with it here, his fundamental question staying the same throughout. He asks this question in the movie too, with the very salient point being "sure, they don't think like we do, but does that mean that they don't think?"

To answer that, we of course have to answer what thinking means, which is not so easy, unfortunately, and, as in many other things, your answer to the original question probably depends on your definition of thinking, but that's a boring and non-saying answer, so I'm going to go a bit more thoroughly through it.

Alan Turing answered this by instead asking another question which you probably know as the Turing Test, which he called The Imitation Game: Can a person tell the difference between a man and a machine, if all they have to go on is responses to questions given to each "person". In other words, can a machine imitate being a person well enough that another person cannot tell the difference. If so, according to Turing, the machine is believed to think.

So far, not a single machine has been able to pass the Turing Test. And not surprising really, when you think about what it takes to do so. It takes a machine that, while it doesn't have to be able to say and know everything an average person does, it probably has to know most of it. Funnily enough, in 1950, Turing predicted that we would be able to create machines that at least came close within 50 years. Well, that didn't happen. Which is a bit sad considering how forward-thinking and sharp he was in most of his thinking (I mean, he was talking about this stuff in the fifties! We still hadn't landed on the moon yet). The Turing Test has been depicted and described in many other stories, movies, games, etc. and it is a widely known example of how different computers tend to act than human beings.

And so enter

The Talos Principle,

a video game released in the weird time of late December 2014, meaning

that most people are playing it in 2015. The Talos Principle is a

"philosophical first person puzzle game" (their words). Think Portal

mixed with philosophy mixed with mythology mixed with some fantastic

world-building and mystery, and you've got a vague idea of just how good

The Talos Principle is.

Now, the interesting thing about The Talos Principle in this context

(because there are a lot of interesting things about this game, but one

thing at a time), is the fact that you are, very obviously, playing as a

robot. A machine. And you get placed in a world, and told by a god

voice to explore and complete challenges for an unknown purpose.

Along your path, you come across computer terminals, which sometime

have archived documents on them that you can access to get a little bit

of a hint of what world you're in and why, but every once in a while,

you are greeted by the "Milton Library Assistant", an AI (presumably)

who is talking to you in natural language, with whom you are having

conversations. In order to get admin rights to the computers (because of

course I want that, right?), I have to prove to this AI that I am a

human being, worthy of being given admin rights. Sound familiar? And

that's just the trick: We're playing, as a human being, controlling a

robot, trying to convince

another robot that we're human. It's the Turing Test, but crooked. That's fascinating.

The way Milton (let's just call it that from now on) deals with your

answers is primarily through logic, which makes sense considering it's a

computer (to be fair, i'm only saying it's a computer because it felt

like one, there might be a plot twist that it actually isn't. I don't

know. And we want to go really meta, it's not a computer at all because

it was written by writers, but let's not go there). Milton is trying to

disprove my points by looking at what I said previously and in true

Socratic fashion use my own words against me. But here's the thing:

People disagree with themselves. When faced with one question I might

say one thing, but when faced with a similar question, posed

differently, I might reconsider my opinion, leading to an

assumed logical fault.

But, taking it further, with me, as a person, knowing that, I might

consider answering more logically, in order to try and trick the

machine, no?

By forcing the player to be a part of the Turing test in this way allows us to see the test from the

machine's side, which is a thing we can only really do in a

game. And while we don't really feel like we're a robot, because we're

still human, it still shows how difficult it is to prove that

I'm a human being, even if I am one, if all I can do it through is words

(which is the requirement for Turing's Imitation Game).

And that's just the beginning of The Talos Principle's foray into these

types of questions. In one of the first audiologs you find, the nature

of which aren't really explained, a researcher talks about how she is

interested in AI, not just in the sense of what we would think about it,

if it actually acted as a person, but what it would think

of itself? Would it consider itself a person? Would it want to

be, whatever that means? The game, by letting you play as a machine,

almost inadvertently answers some of this, since you cannot help but

project humanity into the robot--you want to think it's human, because

after all, you're it, and you're human (right? ;) ).

However, do you say the same of Milton? Of the other AI agents

seemingly on the same path as you, leaving their trails behind in QR

codes and holograms? I frequently had the thought that the messages

might be from other actual players,

Dark Souls style

(since you can write your own messages too), and while that most likely

isn't right (they're simply written too well), it's still interesting

that the game can raise that question from me, because the game is

therefore in a sense, also doing the Turing Test to itself, with

me as the judge. The God who is guiding me around might also,

in fact, be an AI, since there are hints that the entire world is a

simulation, but I don't know that for sure, since I haven't finished the

game yet.

And if it is the case that these are all AI's what makes you say that

you're different from them? The fact that you can think? But didn't we

just show that we can't really prove that easily? So why are you saying

that they can't think?

The Talos Principle is, through it's logic puzzles, lingering questions, and existentialist trials, testing your own feelings on humanity by performing the The Imitation Game on the player, while the player is also inherently judging the game. In this way, The Talos Principle becomes one of the more interesting explorations of The Turing Test I have seen, and while it doesn't necessarily answer the question "Can a machine think" it leaves a startling, nuanced look at what that question really means. Because proving you're human is significantly harder than you might think, if someone has reason to think that you aren't.