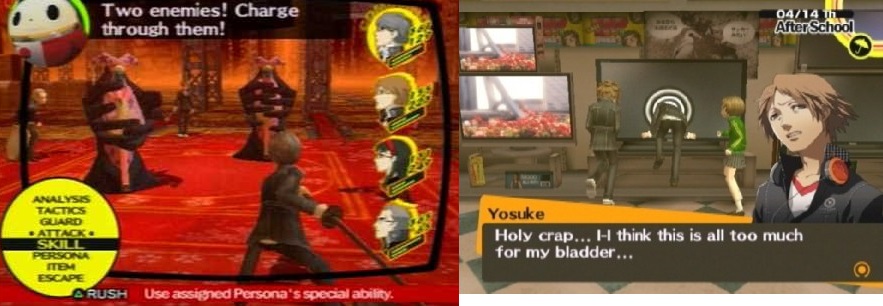

“Yeah, the characters fight monsters inside a TV, but first, they

need something called “Personas”. Which are sort of their other selves.

The side of us we’re unhappy about, that we don’t want to show: That’s

the persona. So, to fight, they need to accept those as part of

themselves, show it to the rest of the team, you know, accept their

weakness. And then they become strong enough to fight monsters…

… Inside a television world.”

Games have a description problem. They’ve had it for a while. Most of

us who play them are, to some degree, aware of it. Or at least, become

aware of it if anyone from outside ever dares peek their head in just

enough to ask that question:

“What are you playing?”

And I sigh. Not because I don't want to explain it. But because how

do I answer that in a way that makes sense, without referring back to

the thirty years of gaming history to which this one game relates and

relies upon? How do I convey this game without falling back to inside

terms and lingo you don’t understand?

And, more importantly, how do

I, instead of relate what the game is, relate what I get out of it? Why I

play it? What it means to me?

To another who plays games, it is easier. We have shorthands, genres,

or other games we can use. Say “it’s like so and so”, or “it’s a platformer with RPG elements”. They know games, so the why is implicit.

But to someone who doesn’t play games? And who doesn’t have that vocabulary?

It seems a nigh impossible task.

But, because I am that kind of person, I want to try. So let us delve

into the impossibility of the adventure, and see where that takes us.

If

you don’t play games, or know someone who plays them, or think you

don’t play games, this article is written for you. If you do play games,

and want to talk about them to those who don’t, this article is also

for you.

I don’t claim to be speaking for all “gamers” (as even that

term is one increasingly debated) but I write from the perspective of

being a lifelong player of games, and as someone who has followed the

game industry for a decade now.

So bear with me. There might be terms you don’t understand. That is fine. You do not need to understand the strange microcosms of games and game culture. I’ll try to explain things, but I’m ingrained and forget what I take for granted. I don’t require you to follow me, I just want to provide you with a picture.

I don’t expect this to be enough. But it’s a start. Hopefully.

What's Wrong? The Many Problems In Describing Games

The first thing you need to understand about describing games is that even the people who know them are bad at it. Just look at our genres, which, to be honest, feel more like broad splashes of paint than useful distinctions of form.

I can already imagine the stares I’d get if I say I’m playing a “roguelike”. What’s that even mean? Well, it’s a game with permadeath and randomly generated levels, that have increasingly less to do with Rogue, the game they still purport to be like. Right? Makes… perfect sense.

Game genres tend to either describe the literal play of a game or the structure it has, but neither of these are any good at describing what the game feels like.

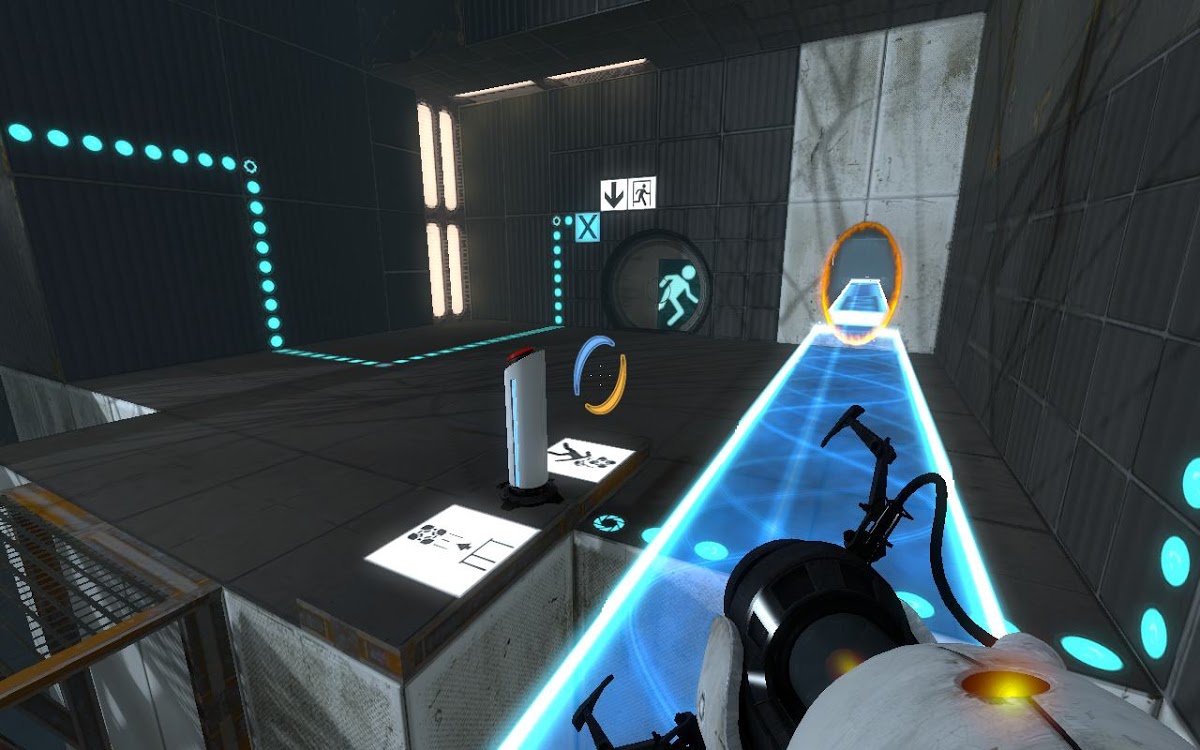

Or take the FPS. You might not know what that is, but if I say it means First Person Shooter, you might have an idea. You’ve probably at least seen one of those. But that’s not even half the picture. Like, how do I explain the differences between Arma, Overwatch and Doom, which are all First Person Shooters, but are so different in style, tone, and play that it’s a disservice to both the genre and the games to lump them all together. Or a game like Portal, where you’re viewing it from a first person perspective, and you’re technically “shooting”, but no one would call it a First Person Shooter. (Portal is, by the way, a “puzzle game”.)

The problem is twofold in the sense that our game genres aren't actually that useful while at the same time so narrow they don’t make sense without you understanding the context of their creation or play.

Game genres tend to either describe the literal play of a game (first person shooter) or the structure it has (roguelike, open world), but neither of these are any good at describing what the game feels like—saying it’s a “novel” doesn't tell you a whole lot about the content inside, and game categories are almost as broad.

But that’s just genres. The problem is deeper than that.

Even if we disregard the problem of “control” for a moment (and that is a vital problem, because most of the barrier to entry for games is that they can be really difficult to control), we still have issues.

There are so many hidden conventions in games, we take completely for granted, that yet we have little to no explanation for.

Why

are we using WASD to move? Why are there so many conveniently placed

red barrels? Why should we always take the less obvious route first? Why

can’t I jump over the fence at the edge of the world? Why can’t I talk

to them instead?

All of these can partially be answered with a “that’s just how games are”, but that’s completely useless to someone who doesn’t know those conventions in the first place.

And secondly, games look impenetrable. Any new game you get,

you are bombarded with a slew of tutorials, UI, “guidances”, modes,

options, dialogue, and whatever else the game feels it needs to explain

before you can play it. Some games are better at this than others, but

more often than not the barrier to even allowing the player to play the game can be high.

This

is done, from the game’s side, to make sure players know how to play

it, and is to some degree vital. Yet, for many modern games, it doesn’t

bother teaching at a level where someone who doesn’t know how to move

two analog sticks could follow along—and to the rest of us, the tutorial

seems superfluous.

I assume most of you have hit one of these walls during your life, and I perfectly understand it. We do not make it easy for you.

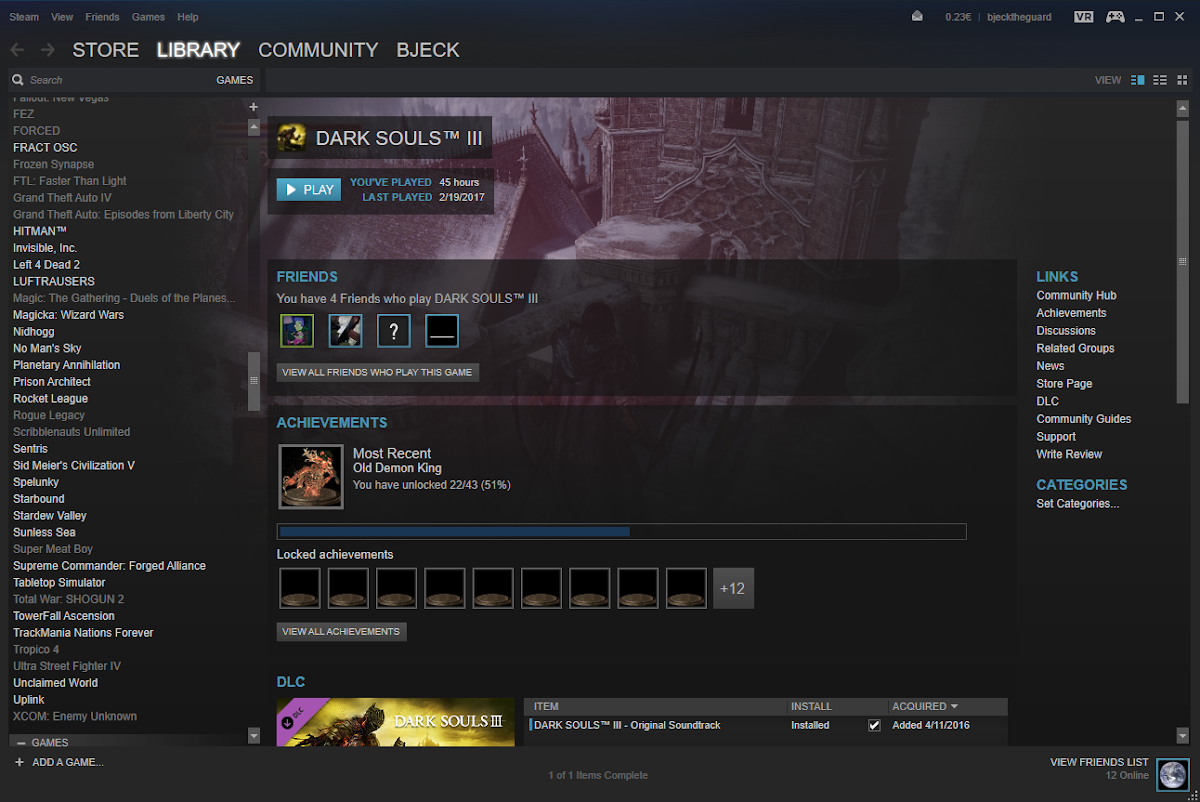

And then finally, the simple path of getting the game is harder than it should be. These days, most games cannot be bought in stores. Most of the games I play would be impossible, or very difficult, to find in your typical store, even game-focused stores like GameStop. Because, increasingly, more and more games are only sold digitally, online. This is especially true of “indie”-games, which are often the most interesting or unique examples of games that provide something different than adrenaline-fueled murder-sprees.

The problem with that is that they are only advertised if you know

where to look. I have a Steam account, so I see which new games come

out, and can filter out which ones look relevant to me. Anyone else have

no idea when Supergiant’s new game “Pyre” will be out, even if they’d really enjoy it, because it never enters a space they view or interact with.

See, I could easily recommend some games for you to try, but the

problem is you can’t just get it easily. Assuming it’s not on console

(where you must have access to the console first), you, on PC, might

need to download a program called “Steam”

first, in which you can then buy the game, and then only access through

Steam. Or you might be able to get it from another storefront, like humblebundle, or itch.io or gog.com.

But you have to go look yourself, which I know stops many, because they

have no idea what to look for on sites like that. And then, even if you

get it, your PC needs to be able to run it. Which means, in a lot of

cases, not having a mac, and having a dedicated graphics card. Phew. You

still with me?

I highlight this long list of problems for two reasons.

One,

because I assume most of you have hit one of these walls during your

life, and I perfectly understand it. We do not make it easy for you.

That you do not feel you have time for games makes perfect sense. Not

only do they take a long time for people who "get" them, starting from

scratch can be an arduous process, with seemingly little return.

Two,

while I don’t expect to solve them all just like that, I think it is

useful to begin understanding the parts of games that lead people to

spend their time elsewhere. I don’t think this list is exhaustive, but

they are all aspects I have experienced or seen people experience.

Because here’s the thing. I really want to be able to do it.

I really want to be able to explain why I find games fascinating, and

not only fun, but enlightening, giving, and a source of joy. I want to

have people experience or at least understand them, to talk about it

with them like you would talk about a good movie or TV show.

To Understand Games, We Need That Context

The problem comes in in that it is really difficult to talk meaningfully about games without knowing those conventions listed above because games use them deliberately as part of their vocabulary. They aren't just accidents. They are part of the game’s message.

I wouldn’t be able to explain to you the deep-rooted implications of the meaning of “BioShock”

(also a sort-of-FPS btw.) without explaining the underlying concepts of

“player agency” and “illusion of choice”. And they aren’t related to

the genre First Person Shooter, but rather to a long history of

singleplayer (play alone) games where the game is telling the player

what to do. None of that is ever specifically referenced by the game, yet it expects its players to understand it.

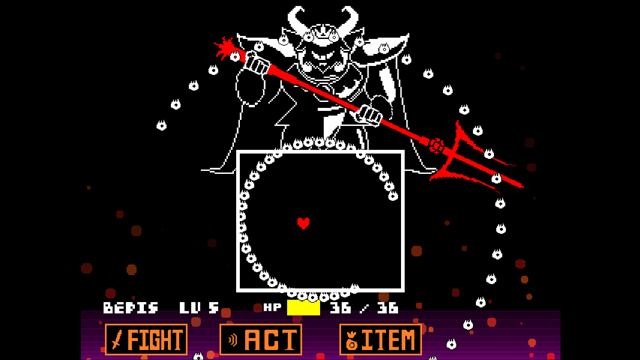

The intelligence and subversiveness of “Undertale” is lost on those who haven’t experienced games doing all the things Undertale subverts—monsters as enemies, battle-systems as number games, the main character as the hero, laissez-faire reactions to killing, etc.

And, to be honest, you could play BioShock and enjoy it without getting that part. Similarly to how you don’t have to deeply analyze a movie to say you liked it. To explain I’m watching a Noir flick, I don’t have to go back and explain to you what “The Big Sleep” is, or give a detailed reason for why there are always hard shadows falling from blinds.

I didn’t play BioShock because I enjoyed the shooting [...] I enjoyed BioShock in spite of it.

But to understand BioShock—and not just play it as frivolous noise-time? You need to have an idea what it’s trying to tell, and that often requires knowledge only people who play games tend to have.

You can understand most Noir because you’ve seen references to Noir film elsewhere. You might miss details, but you won’t miss a reference of a white guy in a hat scowling at the dark, rainy night. Our (western) culture is filled with iconography, meanings, and symbols from movies, books, music—and yes, games—that we recognize and understand in media.

And games do borrow from all that (BioShock

is a (if somewhat lacklustre) critique of Ayn Rand), but the inside

terms that only apply to games? Gaming culture is not as mainstream as

we’d like to think when looking at sales numbers.

And, to complicate it one last step, people come to games for different reasons that might not be obvious from the game itself. I didn’t play BioShock because I enjoyed the shooting, even though that is the majority of the action. I enjoyed BioShock in spite of it, and rather, because the other parts were interesting enough for me to keep waddling through the cumbersome shooting of deranged once-rich people to get to the "good" stuff. But when you see gameplay of BioShock, you’re most likely going to see the shooting. And think “well, that’s not for me.”

The Luxury of Time

Yes, sometimes the reason we play games is just to “shoot some fools” or “rewind a bit”. I imagine many of you also watch plenty of TV because you don’t want to do anything else than ease into something comfortable.

But these days, I go to games increasingly to experience that feeling of, appreciation that comes from seeing a well-crafted piece of art, that comes from understanding the world a little better, that comes from feeling like you’ve changed because you now see the world through a different light than you did before. You know, that.

Some people, I've learned, have no interest in learning how to control a game. That is fine, don’t force them. But we can, instead, show them what we do, bring them in, and have them help and ask them what they want to do.

And we can have conversations about it.

Games have done all of those things for me, and I know for plenty of other people, too.

So how do I share that? Well, I don’t have any definitive answers. But here’s one story:

I had the luxury of time with my parents. Neither of them play games.

But, as I got older and wanted them to not only understand my passion,

but also see it as something they could enjoy, I showed them the games I played. I played and more or less forced them to watch sometimes.

I showed them L.A. Noire because they like 50s noir crime dramas. I showed them Journey because it is a beautiful experience everyone should go through at least once, even if they don’t control it. I showed them Assassin’s Creed because they like history. I showed them Papers, Please,

because it broke my mind over Christmas and I had to talk about it. I

did this, and I think that slowly, over time, they did begin to get it.

They never once sat down and actually played these games—I played for them and they watched—but they were a part of it, and they experienced at least a little of it with me.

Some people, I've learned, have no interest in learning how to

control a game. That is fine, don’t force them. But we can, instead,

show them what we do, bring them in, and have them help and ask them

what they want to do. And we can have conversations about it.

The opening quote of this article is paraphrased from me trying to explain Persona 4 to my mom. (A game I would struggle to explain to anyone.) I never described how to play it, instead I tried to focus on what it did. And I think she got it. After a while.

I think that’s the real key: You don’t need to learn how to play a game to understand them. Rather, we need to be able to talk about it.

And in fairness, I still struggle with that. I’m not sure how to talk about all games, even with people who play them. We’re still very much in the process of developing our language of what games are and what they can be, so bear with me sometimes if I struggle to explain something I’m not even sure how to categorize. It can take some time.

But the luxury of time is one we rarely have. Showing a two minute clip of Metal Gear Solid will either abhor you, fascinate you, confuse you, terrify you, or make you laugh, depending on which part I happen to show. Just like you shouldn’t judge a book off a single sentence, games are long and slow and they take time to fester, and seeing just a snippet without the context can often give the wrong impression.

So in rushed moments, we are often left to verbal explanations, quick, fumbling attempts to convey a 100 hour epic in three sentences, without using any words that would confuse, scare away or otherwise place barriers for dialogue. And that is difficult, and leaves washed-out explanations that fail to convey what we wanted to say in the first place.

I still have that gut-feeling that the only way to actually show them is to have them play, but I know that isn't feasible. It doesn't make sense for a lot of people to do so. So instead, I try something, and most of the time in the past, I have failed, but that doesn't mean I should stop trying, right?

To You, Who Might Listen

You might still choose to not care. But I can tell you now, that

there is a reason games are becoming one of the dominant mediums of the

21st century. And yes, it is, even if you haven’t noticed. Almost every person plays games today. And the reason for that isn't just that they’re fun. It isn't just that they’re escapism and time-wasters.

Games have made me wonder the meaning of choices, they've made me spend countless hours on improving myself through discipline and hard work, they've made me question what monsters and people are, they've made me feel more connected to strangers, they've made me feel like a genius, they've made me explore worlds that spanned for miles, they've made me explore a house of a family I grew to know, they've made me learn and teach and grow.

They've made me do all that. And then, is it such a wonder that I want you to experience the same? That I at least want you to understand?

However, I do acknowledge that most of the burden shouldn't lie on you who doesn't play. It should lie on us, who do.

I do acknowledge that most of the burden shouldn't lie on you who doesn't play. It should lie on us, who do.

It is our task to explain to you why this medium matters. We need to step forward and keep trying and keep trying, because every once in a while, it does succeed and those few times are worth all the rest. We need to remember to be respectful and considerate, to explain our passion with care and intent.

What I ask in return is that you, who don't play, listen, and, just for a moment, open up to your mind that this might be something you could get something out of, if you dared to try. That the two minute glimpse, the old views you have of what games are from your childhood or mainstream advertising is not in fact the whole picture. And that there is more to it, even if you sometimes have to tune out the violence and gunfire.

…We know our medium can still be stupid and immature and painful and closed.

We know. We’re working on it. And we apologize for the incessant shouting while we’re figuring it all out.